Djangonauts don't let djangonauts write Javascript

Published on , under Programming, tagged with python, django, javascript, rants and htmx.

JS Fatigue happens when people use tools they don't need to solve problems they don't have.

― Lucas F. Costa, The Ultimate Guide to JavaScript Fatigue: Realities of our industry

Documents vs Apps¶

90%, if not more, of websites are just documents. They render text, images and forms on your screen. The rest are apps.

Apps have their own needs. They mimic a desktop UI, have custom widgets, need to work offline sometimes and handle lot's of state and complex workflows.

Apps don't feel like they belong to the web. Can you open multiple tabs of the same site? Is text selectable? Can you read a printable version of it? Does back and forth navigation work? Are URLs semantic and bookmarkable? Can screen readers understand your site? Is it crawlable and SEO friendly?

If you say no to most of this questions, then you are in presence of an app, not a web page. Maybe a website is not best suited for this type of projects.

A native app would be better instead of re-implementing entire cross platform libraries and frameworks to work on top of a document rendering engine. Yet the industry has pushed/forced websites to become surrogates of native apps. But this is a symptom of a much deeper problem.

I guess the market fragmentation of OS's is to blame here. Browsers are becoming a layer of sanity on top of all the different platforms and run-times out there, where developers only care about implementing some API's to bridge to the camera, network, disk, etc, built on top of open standards. Webapps become discoverable, portable and easily installable.

But still, the DOM and Javascript lag behind as a cross-platform GUI framework that can replace native apps. Either wasm will fill this gap someday, or Java applets make a comeback, maybe?

Architecture smells¶

Every architecture has a Complexity Budget. It is important to define what the best way to spend it is. What features will need more attention, what's the essence of the application, what purpose it serves, in what problem space it dwells.

Not spending the complexity budget wisely means cognitive overhead in your codebase, over-engineered solutions, accidental complexity, reduced speed of development.

Single page apps (SPAs) are a form of micro services architecture. A decentralized architecture where there are clients and servers.

Micro services in general and client-server architectures in particular are hard to get right. They can be an overkill for most projects, specially websites.

A lot of infrastructure is needed, coordination between specialized teams, multiple points of failure, API deprecation policies, etc, that increase development and maintainability costs. There's a lot that can go wrong.

Just as there are code smells, architecture smells do exists too.

A poor micro services architecture can be detected when in order to develop a feature, you need to touch three repos and instantiate several services to test it locally. In a similar note, if you have to modify the client code along with the server code to reflect a new change in a page and deploy both changes at the same time, it may be that you didn't need a SPA to begin with.

The tight coupling between client and server, or between micro services, is one of those smells that indicates your architecture is still a monolith in disguise.

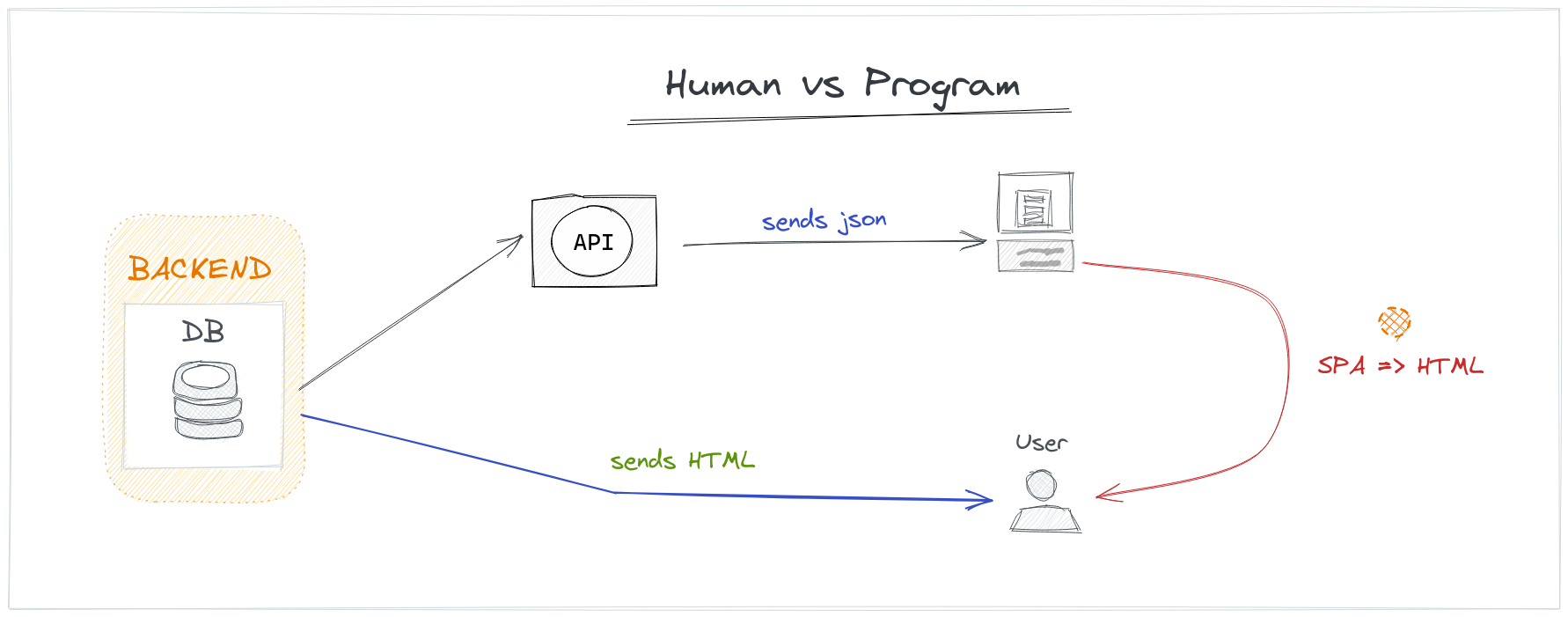

Another architecture smell is using your SPA as the only consumer of your API.

Creating a JSON API just because in the future you might need for other clients like mobile devices or 3rd party apps indicates an early optimization decision. YAGNI.

Restful APIs are usually generic or agnostic from any UI, need to be stable and versioned, etc. Generic APIs might suffer from an expressivity & security tradeoff, because everything you make available to the UI, could also be leaked for malign users. Moreover, this single client SPA requires duplication of logic, models, validation, etc, which the backend will also have to implement since clients cannot be trusted.

The browser is the client you don't have to code¶

Exposing raw data through an HTTP JSON API is really targeted for program to program interaction.

The browser is one special program that doesn't really understand JSON as much as plain text, it only knows how to render and interact with HTML.

When you put the following anchor link in your response:

<a href="/page">Visit page</a>

The browser will eagerly parse the response from the server trying to render the UI on the screen as soon as possible. It recognizes that this tag really is a clickable piece of text that needs to be styled differently, the mouse pointer needs to change we it hovers over it and when clicked a new HTTP request will be issued, the navigation history will be updated, a progress bar will show an indication of a loading state and the result will be finally presented.

All of this default behavior, that users already expect, comes for free if you simply represent your data as HTML. Otherwise, this means more code, testing and bugs to get a similar user experience when you go full SPA mode.

If data is going to be represented as HTML, why not serve HTML directly?

This has the nice property of less time to interactive websites, since there's no need for extra round-trips and hydrate/dehydrate JSON. Serving HTML isn't significantly more expensive than JSON. Like any text format it compresses well, browsers are very performant at parsing and rendering it.

The server describes the UI, it is the single source of truth, it has all the tools it needs to do so and it's cheaper to implement.

You go from using a JSON representation of your data:

{

"account": {

"account_number": 42,

"balance": {

"currency": "usd",

"value": 100.00

},

"actions": {

"deposits": "/accounts/42/deposits",

"withdrawals": "/accounts/42/withdrawals",

"transfers": "/accounts/42/transfers",

"close-requests": "/accounts/42/close-requests"

}

}

}

To using it's HTML representation:

<dl>

<dt>Name:</dt>

<dd>John Doe</dd>

<dt>Account number:</dt>

<dd>42</dd>

<dt>Balance:</dt>

<dd>100</dd>

</dl>

<nav>

<a href="/accounts/42/deposit">Deposit</a>

<a href="/accounts/42/withdraw">Withdraw</a>

<a href="/accounts/42/transfer">Email</a>

<a href="/accounts/42/close">Close</a>

</nav>

This is known as the HATEOAS, just one aspect of REST. We still use endpoints (URIs to locate resources on the web), HTTP verbs to perform actions on them, and HTML to represent those resources.

When using HTML as the technology to render the app state, the browser is the client, not your SPA. User will always get the latest representation of your data, and what can be done with it. It treats synchronous API payloads as a kind of declarative UI language for full state interactions.

You probably don't need a SPA¶

SPAs are hard. If not done correctly, you could be adding megabytes worth of code that need to be downloaded and executed, probably contributing to the current web obesity crisis.

Latest tendencies in the JS world show a comeback to the old ways. Server side rendering so that we don't load a blank page as splash screen, GraphQL as a poor attempt to get back to the trusted backend's SQL, per page hot-loading of bundles trying to break up huge javascript files that bundle entire templates and models that might not be needed everywhere, etc.

This shows little or no benefit to end users of your website, but clearly incurs into costly development cycles: An ever-changing amount of frameworks, tooling (transpilers, bundlers, linters), libraries, DSLs and state management patterns that all compete to be the next hot thing in the industry. This contributes to churn in development teams that need to keep up with the javascript fatigue.

Big frontend codebases have become a liability.

Devs nowadays seem to just skip all this analysis, and are eager to start every project with:

npm install create-react-app graphql

It all comes down to tradeoffs. What's driving these frontend heavy industry standards to be the default go to?

The answer to that could range from peer pressure, job stability, FOMO or probably not knowing other alternatives to create snappy websites.

No JS / Low JS sites¶

As the common proverb says: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun”, server side rendering and static site generators are reviving.

This HTML centric architecture can be a very competitive alternative for interactive websites when modernized with a few tweaks.

The question is, how powerful is HTML alone?

It is very powerful and expressive, and getting better still. We now have async

and defer attributes to load non-blocking <script>'s in parallel,

semantic markup tags to enrich human and program readability,

preload <link> directives for increasing performance of any document

(pre-resolving DNS, pre-rendering another document, etc), the <picture> tag

can be used to load responsive images, <form> elements have native

widgets for things like datetime pickers and validation built-in,

offscreen <img> can be loaded lazily, there's even a built-in toggle

using the <details> and <summary> tags!

But as powerful as it its, it still lacks some directives to make it more dynamic and reactive.

It's not that we need a Javascript everywhere solution for this. But Javascript can help with a progressive enhancement approach, through lightweight and unobtrusive libraries, to provide a smoother experience for end users.

One of such libraries is htmx. It doesn't advertise itself as a JS library, but as a backend agnostic HTML enhancer, extending it's capabilities with custom attributes, lazy loading or partial rendering small sections of the page through AJAX directives and smooth transitions.

<!-- Load from unpkg, jspm.org or skypack.dev, just 10kb, no need for npm! -->

<script src="https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.5.0"></script>

<!-- have a button POST a click via AJAX -->

<button hx-post="/clicked" hx-swap="outerHTML">

Click Me

</button>

In the example above, we can see that we are enhancing the HTML we already

have, with some hx- directives to perform an http post request and replace

the button with the server response.

Perceived performance¶

When loading websites, some latency is expected, but too much can lead users to multi task and abandon the page.

Pages have to load fast, and one of the best ways to make sure that's the case is to make extensive use of caching headers.

But even so, the user might still experience the blink of a full page load.

If instead you use ajax to fetch a link and swap the <body> while you display

a nice animation for the transition.

Similar to what turbolinks does, with htmx, this can be done with

the hx-boost attribute.

<div hx-boost="true">

<a href="/blog">Blog</a>

</div>

This progressive enhancement trick can be improved by using something like Nprogress increase perceived performance.

htmx.on("htmx:beforeSend", function(evt){

NProgress.configure({ trickleSpeed: 100 });

NProgress.start();

NProgress.set(0.4);

});

htmx.on("htmx:afterOnLoad", function(evt){

NProgress.done();

});

The progress bar can be manipulated by changing their speed, so users have something to watch and stay on your page.

Hooking to some htmx events, we can plug our code to display the progress bar.

In this case we show a big first step and then every 100 ms we update the progress until it is completed.

It's turbo time!¶

Although progress bars and ajax links can make your application feel fast, there's a technique that can make it actually be faster.

This technique consists on intelligently pre-fetching links before they get accessed.

When the user hovers over a link it takes about 300ms to actually click the link. Test your own hover timing here. Those wasted milliseconds can be used to preload the contents of the link.

Libraries like instant.page or instantclick are drop-in scripts that take use this strategy. Another interesting strategy is what quicklink offers, which is to load visible links when the browser is idle.

Htmx doesn't lag behind, since it support extensions, you can make use of the

preload directive to trigger it on mouseover or mousedown events.

<div hx-ext="preload">

<a href="/my-next-page" preload="mouseover" preload-images="true">Next Page</a>

</div>

This tools need to be used carefully since you might be over-fetching lots of pages that the user won't ever need, so it makes sense for certain navigation links like main menu or a tabbed pane.

Partial rendering¶

It often happens that the vast majority of the page is static, but there is a tiny portion that needs to be updated in response to an action, like clicking on a paginated list of results.

When htmx communicates with the backend, it sets certain HTTP headers that can be used to render partial content instead without screwing up scroll positions.

In Django land, django-htmx provides some helpers that allow our views to

render different content depending on the request.htmx flag.

def my_view(request):

if request.htmx:

template_name = "partial.html"

else:

template_name = "complete.html"

return render(template_name)

Then in the complete.html template, we can use:

{% extends "base.html %}

{% block main %}

<main>

<h1>Static content that doesn't change</h1>

{% include "partial.html" %}

</main>

{% endblock %}

And in the partial.html template we just include only what is dynamic.

<div hx-target="this" hx-swap="outerHTML">

<p>It is {% now "SHORT_DATETIME_FORMAT" %}</p>

<a hx-get="/my-view/" href="#">Refresh</a>

</div>

A nice addition to using partials, the slippers library lets you write reusable components that can be extended in your in your templates, which are more versatile than what Django offers out of the box.

If the snippet requires more interactivity, like a real time form validation, something like django-unicorn can be a good choice, since it uses morphdom, which htmx also supports to do HTML diffing, which can help preserve the focused element for example, instead of replacing the entire DOM sub-tree.

Async rendering¶

It often happens that the vast majority of the page is generic to every user, but there is a tiny portion that needs to be custom for logged in users, like the "Hi user222" snippet included in most nav bars, which depends on each user being logged in or not.

This is a bummer, since the entire page could be perfectly cachable, if it wasn't for that piece of user specific content.

One way to overcome this is, is to use lazy/async rendering of those snippets.

Other times some parts of the page take more time to load, and it would be better to defer the rendering for later, once the user has loaded the rest of the content.

<div hx-get="/profile" hx-trigger="load" hx-swap="outerHTML">

<img class="htmx-indicator" src="/spinner.gif" />

</div>

The hx-trigger is activated when the element is loaded (but can also accept

other triggers like revealed, intersect, etc). The htmx-indicator class is

used to toggle it's visibility, useful to display some sort of placeholder or

spinner.

Javascript is fine¶

The techniques mentioned are good alternatives to SPA or heavy frameworks, but there is no silver bullet. More alternatives do exist, like alpine or hyperscript, that let you express more UI behaviors within an HTML element.

Some libraries can be included from CDNs like unpkg, jspm.org or skypack.dev and using minimal dependency loaders like fetch-inject, so that no bundlers are required.

When the complexity budget of your project allows for it, there is nothing wrong with using Jquery, React or Vue for certain pages that are inherently complex and dynamic.

</article>¶

Going through my notes, I realized I started drafting this post circa 2017, when I first noticed the JS-all-the-things trend in the industry.

Four years later, the state of things hasn't gotten better, yet projects like htmx are gaining traction for small / hobby projects, which is promising.

Maybe this post inspires you to start your next project as a MPA, instead of a SPA with the framework dujour, to avoid JS fatigue, save time and money.